IN THE NEWS

Boys’ Summer Dance School Press Release

American Dance Student Awarded Scholarship for Study at Unique Program for Boys at the Shore School in Sydney, Australia

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Thursday, November 30, 2017 Contact: Robert Fox

Email: rfox@shore.nsw.edu.au Phone: 61 2 410490710

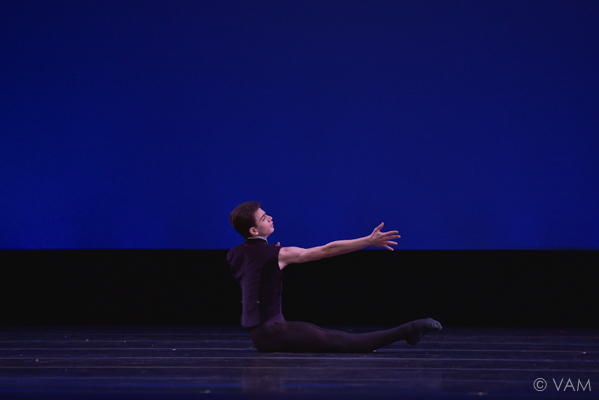

Sydney, Australia: Robert Fox, the Director of the Boys’ Summer Dance School (BSDS) in Sydney, Australia in collaboration with Scott Gormley of NuArts Productions in Williston Park, NY, has selected American dance student Clark Eselgroth to receive a merit scholarship to attend the Boys’ Summer Dance School to be held at Sydney’s famous Shore School for boys in December 2017.

In announcing the Scholarship, Robert Fox said: “I am delighted to have found in the NuArts Foundation a set of objectives that resonates so closely with our own – namely the encouragement of boys to pursue their passion for dance.

In offering this Scholarship in the US and also in the UK, we seek to entrench our Summer School as a truly international event and in so doing provide a unique opportunity for our Australian participants to engage with other boys from around the world who share their passion.”

The Shore School presents the Twelfth International Boys’ Summer School, a full-scale summer intensive conducted over six days by top teachers and choreographers catering to boys all over Australia and beyond who are passionate about dance. BSDS faculty is headed up by Artistic Director Christian Tátchev with Special Guest Tutor Li Cunxin, Queensland Ballet Artistic Director and author of the best-selling autobiography Mao’s Last Dancer (2003). BSDS faculty will also include the talents of Wim Broeckx, Jason Duff, Jacob Williams and Richard Causer.

Royal Ballet Principal Dancer Alexander Campbell, a Sydney native, was recently named the Ambassador for the program. “I am delighted to be the Ambassador for the Boys Summer Dance School at Shore. The Summer School is a wonderful opportunity for the participants to work with world-class teachers and instructors in an environment that is challenging and encouraging. I know from experience that ballet training can be isolation for a male at time, so I am thrilled that this opportunity exists where boys from all over Australia can meet and work together…”

Clark Eselgroth is a 15-year-old dancer who trains in classical ballet at the International Ballet Academy in Cary, North Carolina. He met Scott Gormley, director of Danseur, when Gormley visited the Boys Ballet Summer Intensive, a program similar to the

Shore School’s program, in 2016 to conduct interviews with boys and men involved with the program. Eselgroth’s mentor and choreographer Patrick Frenette is a featured dancer in the Danseur film.

“The NuArts Foundation is dedicated to extending the dreams of young men in ballet,” said Gormley. “Programs like BBSI, Boston Ballet and the Boys’ Summer Dance School are essential to their growth and development as strong and confident DANSEURs.

We are so pleased to have presented Clark Eselgroth as our candidate for this year’s student exchange. Clark is a wonderful example of American ballet talent and displays the drive and determination that it takes to be a successful professional dancer.”

Eselgroth was the 2017 recipient of the Fernando Bujones Living Memorial Award at the American Dance Competition in Saint Petersburg, Florida. Also in 2017, Eselgroth was a Final Round competitor in the Youth America Grand Prix Finals in New York City, where he received

scholarship offers from schools in Europe, Canada and the United States. He has trained at summer intensive programs at Houston Ballet Academy and Boston Ballet School on full merit scholarship. Eselgroth will be accompanied to Sydney by his older sister Lilian Eselgroth, a Muse Scholar at Hunter College in New York City, who will serve the program with photo/video documentation and social media work.

Visit BSDS’s website (http://www.boyssummerschool.net) to

learn more about the program.

Tights, Tutus and ‘Relentless’ Teasing: Inside Ballet’s Bullying Epidemic

“If this were not the arts, it would be considered a child health crisis.”

For years, ballet phenom David Hallberg was bullied. Growing up in South Dakota and Tucson, Arizona, the boy who would go on to become one of his generation’s greatest dancers endured teasing, name-calling, ostracism and physical abuse at the hands of classmates — all because he was a boy who danced.

In Hallberg’s forthcoming memoir, A Body of Work: Dancing to The Edge and Back, the American Ballet Theatre principal dancer describes the joy of discovering ballet and the misery of being bullied for it. He was called a “faggot” and a “girl,” and, on one occasion, boys at school emptied “an entire bottle of cheap drugstore perfume” on him. “Every last drop. In seconds. On my shoulders. My face. My hands. My arms. My clothes … Mission accomplished. I officially smelled like a girl.”

Hallberg found some sanctuary at a performing arts high school, where his love of dance was normal. It offered him and his fellow dancers a “haven where we could be ourselves,” and where the once-tormented dancer and his boyfriend could hold hands without anyone looking askance.

Hallberg’s experience with bullying is the norm for boys who do ballet, whose choice of after-school activity makes them vulnerable to harassment at the hands of classmates and adults — sometimes adults in their own family — who think ballet is an inappropriately feminine pursuit for boys and men.

The statistics on boys, ballet and bullying are staggering. According to a study by dance sociologist Doug Risner of Wayne State University in Detroit, 93 percent of boys involved in ballet reported “teasing and name calling,” and 68 percent experienced “verbal or physical harassment.” Eleven percent said they were victims of physical harm at the hands of people who targeted them because they are boys who study dance.

Much of the teasing and harassment endured by boys in ballet is homophobic, motivated by the perception that ballet is for girls, and that boys who choose to do it must be gay. The epidemic of anti-LGBTQ bullying in schools has earned deserved attention from media outlets and policymakers in recent years, and with good reason: LGBTQ youth aretwice as likely to report being bullied and harassed than their straight counterparts, and that harassment increases the risk of self-harm and suicide. As Risner told HuffPost, the numbers from the ballet world alone dwarf those of the general population. “If this were not the arts,” he said in a phone interview, “it would be considered a child health crisis.”

In Risner’s study, teenage boys reported having been teased “forever” and “ALLLLLLLLLL the time,” and more than half said the most significant challenge they confront as boys in ballet is the harassment that serves to police their masculinity — “the homophobic attitude of some” and “the assumption that ballet is only for girls and gay men.” More than 85 percent said more boys would study dance if boys and men weren’t teased and harassed so much for dancing.

When filmmaker Scott Gormley’s son hit seventh grade, he suddenly became anti-social and withdrawn. “He went from a group of 25 kids that he would hang around with to being home every weekend and only associating with one or two girls. And that kind of struck me funny,” Gormley told HuffPost in a phone interview. Gormley feared the worst — harassment, or, God forbid, sex abuse. Pressed to talk about the change in his behavior, Gormley’s son, who had been studying ballet since he was very young, revealed that “his friends couldn’t accept that he was a dancer,” and had ostracized him from their social group. “I just couldn’t believe that,” Gormley says. “I was flabbergasted that in this day and age people would shun you for wanting to dance ballet.”

Gormley soon discovered that his son was not alone, and decided to explore the idea of making a documentary about the experiences of young boys and men who dance ballet. He found dozens of parents willing to talk about what their sons were going through. “I put out a post on a message board that had many parents on it, and in a matter of hours — not days — I had a full inbox of ‘Oh my God, my son experiences this,’ or ‘You have to talk to so and so.’” Soon Gormley was hearing from adult professional dancers who wanted to tell him about their experiences, and the project ballooned into a full-length documentary film, “Danseur.”

However, not all parents were so willing to talk. Gormley interviewed many boys and young men whose fathers, especially, were unsupportive of their ballet. “There were men whose dads won’t come to performances, or if they were there it was purely window dressing and they weren’t participating. One young man still doesn’t speak to his birth father because of it.” Gormley says. “It shocked me personally because I can’t imagine not supporting my son no matter what he chooses to do. I mean, I have a son who plays hockey and a son who dances ballet. Would I love any one of them any less because they chose to play hockey or dance ballet? It’s a ridiculous notion.”

John Lam, a Boston Ballet principal dancer, says that when he was 14 and was offered a spot at at an elite ballet boarding school in Canada, his father didn’t want him to go. “He said, ‘You have to stay home, I don’t want you to be gay.’ So I said, ‘Okay, I won’t be gay. And I just lied in front of my parents.’” Lam has been a professional dancer for 15 years, and his parents have never seen him perform.

Risner’s findings suggest that Lam’s experience is distressingly common. While boys in their study reported teasing and harassment at the hands of “football jocks” and “sports boys at school who think they are soooooo cool,” many said they get the least support from their fathers. “It’s horrible for these young boys,” Risner says. “They report their fathers, their male siblings, uncles, stepfathers, are the least supportive. And in fact are almost a barrier to their dancing.”

Risner says Gormley’s film captures the contrast between the passion so many boys feel for their art form and the rejection they feel when their fathers don’t support them. “It’s so poignant in the film because you watch these young men, these boys who are so present and engaged and into dance and the physicality and the creative expression,” Risner says, “and then you get them talking about their experiences of bullying and harassment and the lack of support, and you can see that it just wrings them out. They just lose everything. They become ashen.”

Of course, fathers often are supportive of their sons’ passion for ballet. And while many of the boys in Risner’s study report that they get the most support from their mothers, not all mothers are on board with their sons studying ballet. Gormley says he’s been unable to interview at least one boy because his mother refused to sign a release form. Another boy’s mother refused to drive him to his interview, just as she refuses to drive him to ballet class — ever. “It was clear that he was wrestling with not just being a ballet dancer, but potentially being a young gay black man who wants to dance ballet,” Gormley says. “I can’t imagine what he’s struggled with. He’s a gorgeous dancer, too. It was just heartbreaking.”

While many of Risner’s respondents reported that the women in their families are supportive, plenty of girls and women pressure boys to conform to a particular kind of masculinity. One of Gormley’s interviewees says that he’s most viciously teased by girls at school; Hallberg, too, recalls being teased by female classmates.

Sean Aaron Carmon, a dancer at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, told HuffPost that when he was growing up and studying ballet in Texas, the only person who gave him a hard time about dancing, apart from his high school gym coach, was his older sister. “She was so embarrassed because in my mind it was totally fine to wear my dance clothes before and after class,” Carmon said in a phone interview. “She said, ‘Can you please not do that, you look ridiculous and it’s really embarrassing.’” Carmon told her that he didn’t really care what people thought of him, “but then I found myself changing because I didn’t want to embarrass her and I didn’t want to make school hard for her.”

Devin Alberda, a member of the corps de ballet at New York City Ballet, started ballet instruction at age 4. One of his earliest memories of ballet class is that a girl classmate cried because she had to stand next to a boy.

Despite recent shifts in public opinion on LGBTQ issues like marriage equality and adoption rights, the cultural penalties are swift and harsh for boys who transgress gender norms by entering the ballet studio. The popular perception of ballet as feminine means that boys who study it are often viewed with suspicion, and their sexuality is called into question. Risner’s study found that many of the boys who said they were bullied or harassed, be it by school peers or by people in their own families, were subjected to explicit homophobia. “I learned about anal sex from someone telling me I liked it up the ass,” says Alberda, who grew up in Cleveland. “When I was in middle school.”

Other boys and men report being targets of a more generalized misogynistic harassment for their involvement in a pursuit widely seen as being “for girls.” In addition to direct homophobia, Hallberg was mocked for his allegedly girlish voice and gait. For these boys, the line between being called gay, being called girlish and being called a girl is thin, and often blurred, and suggests the extent to which homophobia is often rooted in a disdain for women, girls and all things feminine.

In response to the homophobia and misogyny — the challenges to their masculinity — many argue that ballet is just as masculine, if not more so, than some sports. The boys and men in Gormley’s documentary stress the athletic demands of ballet: how high they jump, how strong they must be to lift their women partners, how much they train and how fit they are. “It takes extreme amounts of training, physical conditioning,” says James Whiteside, a principal dancer at American Ballet Theater. “I go to the gym maybe three or four times a week and lift weights, because there’s so much partnering in ballet, and I want to be strong for my partners.”

Harper Watters, the Houston Ballet demi-soloist, agrees. “I tend to not like to compare to other sports … because it’s just a different world. We’re not slamming our bodies into people … but [other athletes are] not having to lift people over their heads and keep them there.” Jared Tan, a dancer at Atlanta Ballet who teaches boys at that company’s school, says it’s “true” that dancers are just as physically impressive as sports figures. “I told them that too,” he says of his bullies. “I told them, I’m a better athlete than you. I dance every day.” Though they wear tights and move to classical music, they’re really athletes, and therefore, really men.

Others respond by reminding their tormentors that, as ballet dancers, they get to spend lots of time with girls. “My mom would give me lines like, ‘I get to be around girls all day,’” Alberda recalls. Paul Amrani, a 17-year-old ballet student in Iowa City who trained full time for two years at the Houston Ballet Academy, echoed this sentiment. “We get to be around athletic women all day.”

It’s true that boys are dramatically outnumbered by girls in ballet classes. Leslie Nolte, who owns the Iowa City school where Amrani trains, says that of her 1,000 students, 34 are boys. Many of the ballet dancers who spoke to HuffPost about their experiences reported being the only boy in their class, or even in their entire dance school, and said that they didn’t dance with other boys until they left home for the residential programs that gather students from all over the country and feed directly into ballet companies. While these kinds of numbers can make for a good retort to a playground bully, they also result in isolation and loneliness for boys, who go without the kind of peer group affirmation that girls who study ballet so often enjoy.

In Risner’s study, 71 percent of boys said they thought more boys would study dance “if boys/males knew more male friends who dance.”